Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar

1900-1950: The Great Silence

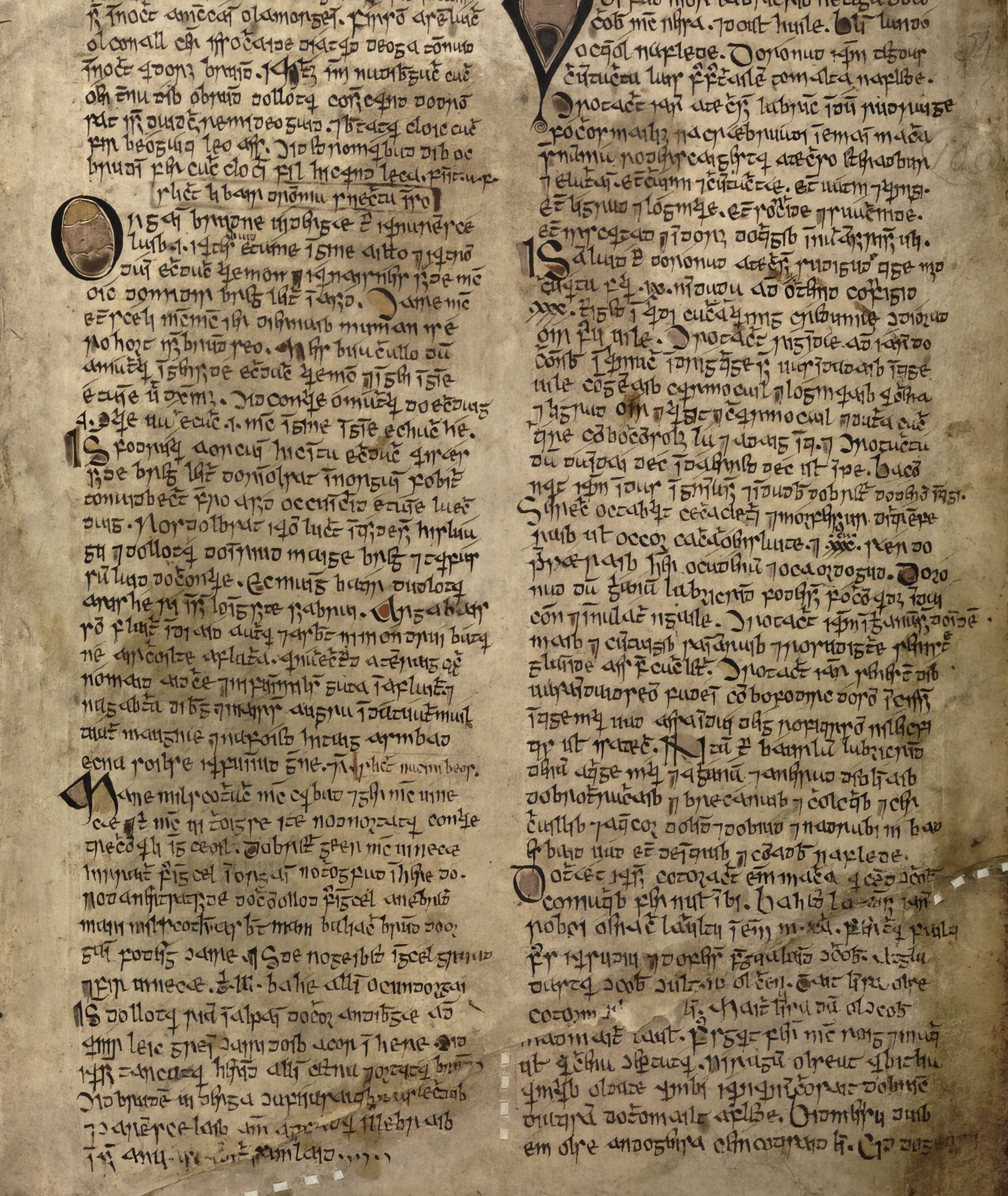

I stand before the Book of Ballymote,

The Book of Leinster, the Leabhar Breac, and last

The oldest, Leabhar na hUidhre – tomes that hold

My people’s history in a thousand ranns:

I cannot read a word.

I do not know the tongue my fathers spoke,

I cannot sing the songs my fathers sang,

I cannot read the books my fathers wrote;

Treasure on treasure in my eager hands:

I cannot read a word.

- Pádraig Ó Broin, “Disinherited” (1)

Despite preservation efforts and continued use in specific communities, the Irish language faced significant challenges in the early 20th century, leading to a decline that affected both transmission and public awareness.

In the 1901 Canadian census, Gaelic or Irish could be listed as the first language spoken at home. This census reveals that Irish had been passed down through several generations of Irish-speaking Canadians. In one studied settlement, Gagetown, New Brunswick, 20% of the population were Irish-speakers, and only a minority had been born in Ireland.(2) The language had survived through adversity on Canadian soil, with records of children also being raised in the language in Québec, Ontario, and Newfoundland. However, many Irish-Canadian children of this era grew up without ever knowing what language their older relatives spoke together, especially in families carrying the trauma of the Famine.(3) Even those who proudly registered themselves as Irish speakers on the census had their entries overwritten by government officials to instead say “English.”(4)

Preservation Efforts

As the use of Irish continued to decline, societies formed to preserve the language in Canada. The Gaelic Revival Association of Ottawa was founded in 1901. The Ancient Order of Hibernians in Ontario, established in 1904, aimed to introduce Irish language education in schools and Irish language books in public libraries.(5) Public lectures on the global revival of the language by Douglas Hyde, the founder of Conradh na Gaeilge in Ireland, drew large crowds, with 1200 people attending in Toronto in a single night in 1906. Gaelic League branches appeared in major cities across the continent, including Toronto, Ottawa, Montréal, Québec City, and St. John’s. Cumann Muinntearach na n-Gaedheal was established in Woodstock, Ontario, in 1908 to create a community among the Irish speakers and writers of North America.(6) It began to distribute An Bád Beag Glas, one of the only entirely Irish-language magazines in the world at the time.(7)

Challenges and Opposition

Efforts to preserve the language faced opposition from mainstream English Canadian society. Newspapers vilified Gaelic Leaguers, labeling them as Fenians, terrorists, or misguided idealists. By the First World War, Irish newspapers were banned in Canada as seditious.(8) Many Canadians helped the war effort by joining Irish regiments, and communities across Canada suffered heavy losses. During the Second World War, the Government of Canada banned Gaelic (Scottish or Irish) from all public telecommunications systems.(9) With pressure from all sides, transmission of the language rapidly declined. The language didn't merely fade away due to neglect; it was actively concealed out of shame, as Proinsias Mac Aonghusa noted:

“Could it have happened so gradually that it went unnoticed? This would appear to be most unlikely...Were the children of the original settlers ashamed of the fact that their parents spoke English poorly and used a foreign language among themselves? Did they deliberately hide this ‘shameful’ fact from their children and so on? It is difficult to think of other likely explanations.”(10)

Disappearance and Legacy

The Irish language virtually disappeared from public consciousness during the 20th century. In the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland, some households continued to use Irish after the First World War, but the unique local dialect of Irish at some point ceased to be spoken.(11) The language had become so marginalized and ignored that its decline went largely unnoticed by English or French Canada. By the 1931 census, the language had collapsed in Canada, with only isolated cases of children being raised with Irish. The devastating social outcomes of language and culture loss are now recognized, though little research has been done on the effects within the global Irish diaspora.(12) In Canada, the Irish language became a shameful secret, hidden from children behind closed doors. This was the experience of Dr. Peter Toner, who grew up around Irish speaking families in New Brunswick:

“It was a “secret” language in my time, not spoken outside the home, or when others were in the house… The language was seldom spoken when anyone else was around, but once they left, "jabber, jabber" mixed with gossip about the departed company…”(13)

For citation, please use: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall. 2024. “1900-1950: The Great Silence.” Na Gaeil san Áit Ró-Fhuar. Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir: www.gaeilge.ca

Any views expressed are those of the author alone, and may not reflect the views of Cumann na Gaeltachta. Any intellectual property rights remain solely with the author.

-

This section’s title is in reference to De Fréine, Seán. 1978. The Great Silence. Dublin: Mercier Press.

Image citation: Ottawa University (1901) (Ottawa Gaelic Society). Adapted from: Library and Archives Canada/Topley Series E/ 936-270 NPC.

199th Battalion, The Duchess of Connaught's Own Irish Canadian Rangers. Adapted from: Library and Archives Canada/ 1964-114 NPC.

Pádraig Ó Broin. 1936. “Disinherited.” Pádraig Ó Broin (J. Patrick Byrne) Papers. Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library (Toronto. MS Coll 00247). This poem was first published in Writer’s Studio, 1936.

Of this poem, Ó Broin wrote: “The first time I was in the University of Toronto Library stacks I took down from the shelves three huge tomes, facsimilies of Gaelic manuscripts, and leafed through them. At the time I couldn’t read a word of Gaelic and out of that bitterness came this poem.”

As Jonathan Dremblins notes, Gaelic speakers, both Scottish and Irish, were prevalent enough to receive explicit mention in the census instructions. See: Gaunce, Bradford. “A Case Study on Irish Language Survival in Gagetown, New Brunswick.” Diss. University of New Brunswick, 2013.

Seán Ó Ríordáin, born in Ottawa, Ontario, recounted in 1953: “Ní thuigeann mo thuismitheoirí Gaeilg ar bith. Thuig athair mo mháthar Gaeilg go maith, ach níor mhúin sé Gaeilg ar bith dá chlann. Do léios leabhra Éireannaigh nuair bhíos im pháiste, leabhra scríofa i mBéarla [Sacsan]. Do ba leabhra staire agus filíochta iad a bhí ag m’athair, ach is dócha níor léigh sé féin iad. Chuir siad grá Éireann im chroí, nó, b’fhearr do rá, do mhéadaigh siad grá na hÉireann a bhí ansin ó thús. Bhí bród agus grá Éireann ag mo thuismitheoirí, ag mo mháthair go háithrid, ach ag an am céanna, níor dhéinidís rud ar bith a ghoilleadh ar Shasana. Sin é an cás ag formhór na muintire Éireannaigh a bhfuil fios agam orthu, agus is ait an treo aigne é sin, dar liom.” (Teangadóir. 1953. 1 (1). Cló Chluain Tarbh: Toronto.)

Gaunce, Bradford. “A Case Study on Irish Language Survival in Gagetown, New Brunswick.” Diss. University of New Brunswick, 2013.

Meeting in St. Thomas, their resolution of August 1904 stated “That we, the members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians of the Province of Ontario are of the opinion that Irish history and the Irish language should be introduced into our Separate Schools, and that books relating thereto should be placed on the shelves of the free libraries of this Province, and recommend that the officers and members of all Divisions of the Order in the Province endeavor to carry this opinion into operation.” McLaughlin, Robert. 2013. Irish Canadian Conflict and the Struggle for Irish Independence, 1912-1925. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

The Cumann was founded “to bring about a closer acquaintance, and to cultivate friendship among the Irish speakers and Irish writers in America… it appeals to all lovers of the Irish tongue to join us and co-operate with us in our efforts on behalf of our native speech...” The society was entirely non-partisan, non-political and non-sectarian. Its foundational documents state that any Irish speaker, man or woman, could become a member, and anyone habitually using English would be stripped of their membership.

A circular subscription, an editor was elected for each issue and it would be sent from one member to the next, with each member receiving it adding to it a short essay, story or poem in Irish. “No member need feel any reluctance about contributing to this, as no other member is allowed to write any corrections or criticisms on the face of the article; but every member is requested to write personally and privately to every contributor and correct any errors in his style or grammar. In fact, the chief purpose of the magazine is to give the members an opportunity to increase their familiarity with and their command of their native language. We hope in this way to educate a group of writers that Erin will be proud to call her children.” As a unique snapshot of the Irish speaking population of Canada at the time, even a single issue of this magazine would yield invaluable insights into the remaining Irish Gaelic culture of Canada at the time. However, due to the nature of the magazine’s format it is unknown and unlikely that any issues still exist.

In 1915, two weekly newspapers publishing material in Irish Gaelic, The Gaelic American and The Irish World, were prohibited in Canada due to seditious materials calling for a free Ireland and the resuscitation of the Irish language and Gaelic culture. Any person found with these papers was liable to a fine of $5,000 or five years’ imprisonment.

Ireland had only gained independence two years before the war, and with little money or military stocks remaining had declared itself officially neutral. The Government of Canada believed this neutrality was actually covert support for Nazi Germany, and extended the ban to Cape Breton Gaelic, amid much backlash from speakers there.

Mac Aonghusa, Proinsias. 1988. “Reflections of the Fortunes of the Irish Language, with Some Reference to the Fate of the Language.” The Untold Story: The Irish in Canada. Ed. Robert O’Driscoll and Ed. Lorna Reynolds. Toronto: Celtic Arts of Canada.

Fáinne an Lae. 1925. Uim 279 (23 Bealtaine). Cló Oifig Mhuintir Chathail: Áth Cliath. “Adeir Donnchadh Ó Cuinn, 89 Cnoc Chartuir, San Seán, Talamh an Éisc, go bhfuil bailte ansin go fóill mar a labhrann na Gaeil atá iontu an Ghaeilge i gcónaí. Nach hé an feall é nach bhféachtar lena bhfuil de Ghaeilgeoirí san Oileán Úr ar fad a chur i gcumann le chéile, le go mbéadh meas acu ar a n-urlabhra dílis féin is go mbuanóidís é.“

“Donnchadh Ó Cuinn, 89 Carter’s Hill, St. John’s, Newfoundland, says that there are houses there still in which the Gaels in them still always speak Irish. Isn’t it a treachery that it isn’t seen by Irish-speakers in North America to be associated with each other, so that they would have esteem for their own loyal speech and that they would preserve it.”

“Linguistic colonisation is as near to complete colonisation as is possible. A cultural blindness descends on its victim, an inability to perceive his original universe and its structures as even his immediate ancestors saw them… The personal and cultural possibilities inherent to the mother tongue are no longer available to the colonised and are replaced by those of the coloniser’s language. The linguistically colonised, whether patriot, a seeker of political freedom, or not, is now imprisoned in the referential universe of the domesticated acculturated colonised. No longer able to self-define in terms of his ancestral tongue, nor even interested in doing so, the colonised can only now do so in terms of the image of himself that he sees mirrored in the coloniser’s tongue. These may not always be phrased in flattering terms but in any case his original power to self-define is now all but lost. A universe has disappeared and another one, a foreign one, has magically taken its place.” Mac Síomóin, Tomás. 2020. The Gael Becomes Irish. Independently Published: Dublin. 32.

Doyle, Danny. 2015. Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. Borealis Press: Ottawa.

All other cited references, numbers, or quotations as from: Ó Dubhghaill, Dónall (Doyle, Danny). 2019. Míle Míle i gCéin: The Irish Language in Canada. 2nd Ed. Boralis Press: Ottawa.

An Bad Beag Glas

Produced in 1909 by Cumann Muinntearach na n-Gaedheal of Woodstock, Ontario. Their rules welcomed “Any Irish speaker or student, who is able to express himself clearly in written Irish” and warned that “Any member habitually using English in his correspondence may be dropped from membership. Women were eligible to membership on the same conditions as men.

One of the earliest commercial recordings of Uilleann Pipes, this record was originally owned by John and Cora Card, of Tamworth, Ontario (now the home of Gaeltacht an Oileáin Úir).

An Chéad Dán

Part of the Toronto, Ontario, poet Pádraig Ó Broin’s 1936 composition, describing his desire to be a Gaelic poet and his experience of being discouraged by others. Handwritten by him in the Gaelic script.